Download the memo in PDF format.

Introduction

For the past twenty years, policy and legislative reactions to the 9/11 attacks have created a web of laws and regulations that have had the counterproductive effect of restricting important humanitarian, peacebuilding and human rights work. Hundreds of nongovernmental and nonprofit organizations (NPOs) have encountered problems accessing funds, halted programs because of concerns that their work would cross legal boundaries, and been shut out of regions and to populations that are in dire need of assistance.

The Charity & Security Network, a community of hundreds of humanitarian, peacebuilding, human rights and civil liberties groups, looks forward to working with the Biden/Harris Administration and the new Congress to update the current legal framework and resolve these long-standing problems. In some cases, little more than executive remedies are needed to greatly ease and facilitate urgent programs. In others, Congress needs to act to clarify and provide legal safeguards that allow thee organizations to carry out their essential work.

This document lays out our recommendations to resolve these issues and facilitate improved processes, legal rights and an enabling environment for nongovernmental programs that aid those most in need. It also provides an opportunity to for the United States to reclaim is mantle of international leadership on issues of international peace and security. For example, these recommendations would bring , the U.S. legal framework into alignment with international standards, such as the Financial Action Task Force’s Recommendation 8 on Nonprofit Organizations and UN Security Council Resolution 2462.

Summary of Recommendations

The following list summarizes our recommendations for Congress and the Executive Branch. The specific mechanisms to effect these changes are described below in the body of this document.

For Congress

Adopt Safeguards for Peacebuilding and Humanitarian Assistance in the Material Support Prohibition

1) Amend the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA)

2) Amend the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

Safeguards for Peacebuilding and Humanitarian Assistance in Sanctions Programs

1) Restore the humanitarian exemption in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

For the Executive Branch

1) Restore the humanitarian exemption in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

2) Department of Treasury: Issue a General License for Peacebuilding

3) Administration: Issue Executive Order restoring the humanitarian exemption in IEEPA

4) Address NPOs’ Lack of Financial Access

5) Provide adequate due process for U.S. persons and entities added to Treasury’s SDN list

Charity & Security Network Priorities

For Congress

Adopt Safeguards for Peacebuilding and Humanitarian Assistance in the Material Support Prohibition

The root of nearly all impediments to nongovernmental humanitarian, peacebuilding and human rights programs is the “material support” definition that is codified in law and permeates the policy culture of anti-terrorism thinking. Clearly, providing substantial assistance to terrorists is to be prohibited and prevented. However, material support is poorly defined and is broadly interpreted in such a way that it can – and has been – applied to the most incidental and minimal contacts or transactions with individuals or groups. Thus, amending the laws that contain and define this phrase would provide significant clarity and support to humanitarian, peacebuilding and human rights operations.

1) Amend the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA)

Proposed legislative text:

It is the sense of Congress that humanitarian organizations, acting in good faith and with the appropriate restrictions and controls in place, should not be prevented, directly or indirectly by Executive Orders or counter-terrorism laws, from accessing and providing aid to civilian populations before or during humanitarian crises, such as the famine in al-Shabaab-controlled areas of Somalia in 2011 or the chronic food emergency due to the war in Yemen. It is the sense of Congress that peacebuilding organizations [and experts], which aim to prevent, mitigate, and resolve violent conflict, help create the conditions for locally-led efforts towards sustainable peace, and promote democracy, human rights, and stability, all of which serve the United States national and international security interests more broadly, when acting in good faith and with the appropriate risk management in place, should not be prevented, directly or indirectly by Executive Orders or counter-terrorism laws, from providing training, technical advice and assistance, and services to all interested parties participating in efforts to create durable peace.

It is the sense of Congress that peacebuilding organizations [and experts], which aim to prevent, mitigate, and resolve violent conflict, help create the conditions for locally-led efforts towards sustainable peace, and promote democracy, human rights, and stability, all of which serve the United States national and international security interests more broadly, when acting in good faith and with the appropriate risk management in place, should not be prevented, directly or indirectly by Executive Orders or counter-terrorism laws, from providing training, technical advice and assistance, and services to all interested parties participating in efforts to create durable peace.

Amend 18 USC 2339B

(new legislative text in itallics)

“(j) Exception.—No person may be prosecuted under this section in connection with the term ‘personnel’, ‘training’, or ‘expert advice or assistance’ if the provision of that material support or resources to a foreign terrorist organization was:

(1) approved by the Secretary of State with the concurrence of the Attorney General. The Secretary of State may not approve the provision of any material support that may be used to carry out terrorist activity (as defined in section 212(a)(3)(B)(iii) of the Immigration and Nationality Act).”

(2) a transaction or transactions by a person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States with a foreign person that is subject to sanctions under this Act that are customary, necessary, and incidental to the donation or provision of goods or services by the person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States or its foreign representatives to prevent or alleviate the suffering of such civilian populations if:

(A) the person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States has acted in good faith without intent to further the aims or objectives of the foreign person and has used its best efforts to minimize any such transactions; and

(B) the goods or services provided to the civilian population are limited to articles such as food, clothing, and medicine and are not capable of being used to carry out any terrorist activity.

(3) speech or communication if such speech or communication with a Foreign Terrorist Organization is in furtherance of the following:

(A) programs to alleviate or prevent the suffering of or harm to civilian populations;

(B) reduce or eliminate the frequency and severity of violent conflict and its impact on civilian populations;

(C) atrocity prevention;

(D) peace processes or initiatives;

(E) demobilization, disarmament, rehabilitation, or reintegration programs; and

(F) removal of landmines.

2) Amend the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

Use the AEDPA amendment language above to protect against sanctions enforcement for the specified humanitarian and peacebuilding activities, amending 50 USC 1702(b)(2), which currently allows the President to cancel safeguards for certain forms of humanitarian assistance.

Safeguards for Peacebuilding and Humanitarian Assistance in Sanctions Programs

1) Restore the humanitarian exemption in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

Although the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA) has a humanitarian exemption,[4] since 9/11, most terrorism-related Executive Orders (EOs) issued under IEEPA use its authority to cancel this exemption, without stating a basis for such action or setting time limits.[5]

The humanitarian exemption in IEEPA bars the president from blocking “donations of food, clothing and medicine, intended to be used to relieve human suffering,” unless the president determines that such donations would “seriously impair his ability to deal with any national emergency,” are “in response to coercion” or would “endanger Armed Forces of the United States.”[6] This national emergency exception was invoked as the basis for cancelling the humanitarian exemption in EO 13224, signed by President George W. Bush on Sept. 24, 2001.[7] It has since become routine for the humanitarian exemption to be cancelled in Executive Orders. [8]

By cancelling the humanitarian exemption, EO 13224 placed humanitarian aid on the list of prohibited transactions with designated terrorist organizations, affecting everything from negotiating access to civilians to coordinated rescues during earthquakes and floods.[9]

Amend 50 USC Sec 1702 Subsection (a) of Section 203 of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act by adding the following new paragraph at the end:

‘‘LIMITATION ON POWER TO CANCEL HUMANITARIAN EXCEPTION.- Subsection (b)(2) of IEEPA (50 USC 1702(b)(2) is amended as follows:

i. By deleting subsection (A) and replacing it with the following: “aid would not reach civilian populations” and

ii. adding “and ensures that (D) such limits must be temporary and proportionate to the security threat. The President must report to the appropriate Congressional committees in the need for such action and what steps are being taken to reinstate the exception.” The amended law would then state:

(new legislative text in italics)

50 USC 1702

(B) EXCEPTIONS TO GRANT OF AUTHORITY

The authority granted to the President by this section does not include the authority to regulate or prohibit, directly or indirectly— (2) i. donations, by persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, of articles, such as food, clothing, and medicine, intended to be used to relieve human suffering, except to the extent that the President determines that such donations (A) would not reach civilian populations”, seriously impair his ability to deal with any national emergency declared under section 1701 of this title (B) are in response to coercion against the proposed recipient or donor, or (C) would endanger Armed Forces of the United States which are engaged in hostilities or are in a situation where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances and ensures that [2 (D) “such limits must be temporary and proportionate to the security threat. The President must report to the appropriate Congressional committees in the need for such action and what steps are being taken to reinstate the exception.”

For the Executive Branch

1) Restore the humanitarian exemption in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

Using its current authority under 18 USC 2339B(j) the Secretary of State, with concurrence of the Attorney General, should issue the following notice: Approval of Peacebuilding Activities The Secretary of State, pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 2339B(j), having consulted with the Attorney General, orders that the provision of expert advice or assistance, training, and personnel designed to reduce or eliminate the frequency and severity of violent conflict, or to reduce its impact on noncombatants, are exempt from the prohibition in 18 U.S.C. 2339B, so long as the advice, training or personnel are intended and designed to further only lawful, peaceful and nonviolent activities.” Such activities include:

- Expert advice or assistance that facilitates dialogue and promotes opportunities for parties to armed conflict to discuss peaceful resolution of their differences, and logistics necessary to support such dialogue.

- Training, including in-person, written and virtual presentations, aimed at demonstrating the benefits of nonviolent methods of dispute resolution and providing the skills and information necessary to carry it out.

- Expert advice, assistance and dialogue aimed at increasing the human security of noncombatant civilians under international humanitarian law, and logistics necessary to carry this out.

2) Department of Treasury: Issue a General License for Peacebuilding using same language as 2339B(J) safeguard above

3) Administration: Issue Executive Order restoring the humanitarian exemption in IEEPA

The administration should restore the humanitarian exemption that has been cancelled by Executive Order by issuing a new EO with the following proposed Executive Order:

The prohibitions in the EOs listed in the Annex to this Order shall not exclude donations, by persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, of articles, such as food, clothing, and medicine, intended to be used to relieve human suffering, except to the extent that the President determines that such donations

(A) would not reach civilian populations, (B) are in response to coercion against the proposed recipient or donor, or (C) would endanger Armed Forces of the United States which are engaged in hostilities or are in a situation where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances; and ensures that (D) such limits must be temporary and proportionate to the security threat.

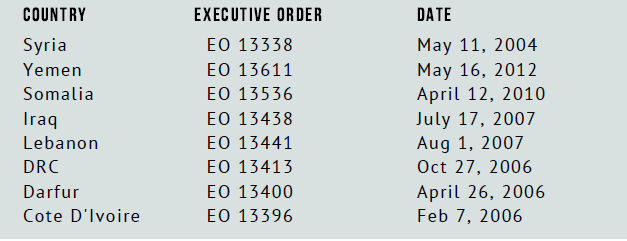

Annex

EO 13224 (Sept. 25, 2001) and EO 13886 (Sept. 10, 2019)

Include, but not be limited to, a list of counterterrorism-related EOs relating to the following crisis areas:

4) Address NPOs’ Lack of Financial Access

A 2017 empirical study found that two-thirds of U.S.-based NPOs face difficulties in accessing financial services,[11]with the most common problem being delays in wire transfers. In focus group sessions conducted to supplement the statistical data in the report, NPO participants noted that delays typically lasted weeks or even months, severely impacting time-sensitive programming. [12] “When programs are delayed or canceled because of the inability to transfer funds, peace is not brokered, children are not schooled, staff is not paid, hospitals lose power, the needs of refugees are not met and, in the worst cases, people die.” [13] While the same study found smaller numbers of NPOs struggling with account closures or refusals to open accounts (15% in total[14]), the impact on NPO operations is significant.”

Many banks and regulatory officials are unaware of the risk assessment and due diligence measures NPOs routinely undertake, not only to comply with sanctions and CFT regulations, but also to account to donors and manage risks to operations and employees.[15]

There has been a shift in the perception of terrorism financing risk in the NPO sector over the past 20 years, from the notion that NPOs are “particularly vulnerable” to terrorist abuse to recent U.S. Treasury statements that the vast majority of US-based NPOs are not high risk for terrorist financing and emphasizing use of the risk-based approach.

While welcome and important, these statements do not have the force of law or regulation. As governments’ understanding of the sector has evolved, that progress has not been reflected in NPOs’ ability to access the financial services necessary to carry out their vital programming. Instead, the global phenomenon known as “derisking” has become, for most NPOs operating abroad, a significant hurdle and for many, an existential crisis. (Please see Annex to this letter for examples.) Although there are likely multiple drivers of the derisking crisis, the failure of the regulatory structure to keep pace with the evolving understanding of the sector is an important factor.[16]

Recommendation:

To provide clarity and a level of assurance that will encourage FIs to manage rather than avoid any real risks posed by NPO clients, U.S. Treasury should update guidance and other documents on due diligence for FIs.

Treasury should ensure consistency and effectiveness in its recent statements about the NPO sector across all of its communications so that FIs regard all of them with the utmost importance:

- Treasury and the FFIEC regulators should update the NPO sections of the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual[17] at the earliest possible date. In October 2017, a group of NPOs and FIs came together to draft proposed revisions to the NPO sections of the Manual, which were then submitted to the FFIEC regulators. We continue to hear from the financial sector that there is a disconnect between the increasingly good statements made by Treasury officials and what they hear from examiners. Until the Manual is updated and bank examiners are trained on this material, FIs will not have the reassurance they need from examiners to manage rather than avoid any actual risk posed by NPOs.

- Treasury and the FFIEC regulators should publish the November 2020 Fact Sheet on Bank Secrecy Act Due Diligence Requirements for Charities and Non-Profit Organizations as guidance.

Treasury should ensure that all guidance and fact sheets reflect the agency’s outreach with the nonprofit and other sectors.

- Treasury should develop a formal mechanism to solicit input from NPOs and FIs on all guidance, fact sheets and other formal statements relating to financial access for NPOs before they are published.

Treasury should make clear to FIs the boundaries of due diligence obligations under CFT law and policy, and ensure that disinformation does not cloud the regulatory landscape.

- Treasury and FFIEC regulators should clarify to FIs that they need not engage in negative media searches, due to the likelihood of disinformation creating an inaccurate “red flag.” FIs’ due diligence should fall within the scope of verified, factual information, such as information contained in U.S. government or United Nations lists such as U.S. Treasury’s Specially Designated Nationals list. (The U.S. Agency for International Development recently changed its contract and certification process to clarify that grantees need only check U.S. government and UN terrorist lists when screening partners and other persons and entities, among other changes.[18])

- To avoid duplication of efforts and resource misallocation, Treasury and the FFIEC regulators should communicate that the due diligence and risk mitigation measures deemed sufficient to receive U.S. government grants are adequate to satisfy those specific elements of the due diligence requirements by FIs. Treasury and the FFIEC regulators should indicate in guidance that FIs can accept documentation from NPOs indicating that specific organizations, implementing partners, sub-grantees or other parties to or aspects of the grant-implementing program have demonstrated and satisfied adequate compliance for the same elements of an FI’s due diligence.

To ensure that the U.S. government’s voice is heard, Treasury, the FFIEC regulators, the U.S. Department of State, USAID, and other government entities should participate in good faith in any U.S.-based multi-stakeholder dialogue on bank derisking, including any new such effort based on the lessons learned and best practices of similar dialogues in the UK and elsewhere. As part of this or as a separate workstream, U.S. government entities should take steps to ensure that the actual risk posed by NPOs operating in sanctioned countries or where listed terrorist groups are present should not be carried disproportionately by any one stakeholder group.

Finally, to ensure that the provisions of the AML Act of 2021 relating to bank derisking are robustly implemented, U.S. Treasury should provide the NPO sector with a timeline and entry points for stakeholder input for the Congressionally imposed requirements around derisking, regulatory review and revisions, and bank examiner training contained in the Act.

5) Provide adequate due process for U.S. persons and entities added to Treasury’s SDN list

Current sanctions resolutions do not address the issue of what happens when sanctions laws, designed to be imposed against foreign countries, entities

and persons, are applied to persons with the ability to bring Constitutional claims. This occurs when Executive Orders allow Treasury to designate those who it believes provide support to or are “otherwise associated with” sanctioned parties. During the George W. Bush administration nine U.S. charities were listed as such supporters, and had their assets frozen without the right to meaningful appeal. The two most recent court cases to address this issue found that the process, as applied to these organizations, is inconsistent with the Fourth and Fifth Amendments. The regulation has not been revised to address this issue. (See https://charityandsecurity.org/analysis/mind-the-gap-when-it-comes-tononprofits-the-tax-code-and-sanctions-regime-are-in-conflict/)

Recommendation:

Amend 31 CFR 501.807 to add a section on due process protections for U.S. persons:

(e) DUE PROCESS FOR PERSONS WITH THE ABILITY TO BRING CONSTITUTIONAL CLAIMS

(1) WARRANT REQUIREMENT FOR PERSONS WITH THE ABILITY TO BRING CONSTITUTIONAL CLAIMS.—

The assets or other property owned in whole or in part by any person with the ability to bring Constitutional claims, shall not be frozen, blocked and their possessory interest in property shall not be interfered with, without a warrant based on probable cause issued by a neutral magistrate.

(2) NOTICE REQUIREMENT.—

As soon as practicable following any action pursuant to this regulation, and in no event later than 7 days after such action, the president shall provide notice to any property or property interest of a person with the ability to bring Constitutional claims is made subject to such action. Notice shall include—

(A) the unclassified administrative record upon which such action is based; and

(B) an unclassified summary of any classified information in the administrative record, which summary is sufficient to provide the subject of the action with meaningful notice of the factual basis on which the action was taken.

(3) HEARING REQUIREMENT.—

Within 90 days of any action pursuant to these regulations, which time period may be extended by mutual agreement of the parties, any person with the ability to bring Constitutional claims whose property or property interest is made subject to such action shall be afforded an in-person administrative hearing and may provide documents and other written submissions for the record.”

(4) PROTECTION OF CHARITABLE FUNDS.—

(A) NOTICE TO CHARITIES; OPPORTUNITY FOR COMPLIANCE – In any case which anticipates imposing asset blocking on a U.S. charity recognized as exempt under Sec. 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, before imposing the sanction, the charity shall be notified in writing, by delivery to the chief executive officer or chair of the governing body of the charity, of the facts, events, persons, and other relevant information serving as the basis for imposing the sanction, and setting forth the steps the charity may take to avoid imposition of the sanction. The charity shall have ten days to respond to the government’s proposed steps to achieve compliance.

(B) CHARITIES – If probable cause is found to block the property of a charity the court shall appoint a conservator to oversee the charity’s funds, for the purpose of ensuring that funds are spent for charitable purposes only and that assistance to innocent beneficiaries is not unduly withheld or interrupted.

Protecting Charitable Assets for Charitable Purposes, Due Process In addition to the specific recommendations above, the Charity & Security Network strongly supports the recommendations that our colleagues have offered to the Biden/Harris Administration that address the same and related issues. Specifically, we support recommendations submitted and published by the Alliance for Peacebuilding, Friends Committee on National Legislation and InterAction that related to the issues discussed in this memo. We also endorse the following proposals from the liftsanctionssavelives.org coalition.

1) Require impact assessments of sanction programs (including humanitarian impact)

High COVID-19 related death rates in heavily sanctioned countries illustrate the grave consequences of deficient healthcare infrastructures, weakened in part by sanctions. In 2019, the Government Accountability Office issued a report that noted, “[s]anctions may also have unintended consequences for targeted countries, such as negative impacts on human rights or public health.” In addition, the report concluded that unilateral sanctions measures are difficult to assess and are not necessarily effective in achieving foreign policy aims. We urge the implementation of regular assessments to better understand the human costs of sanctions and whether sanctions are effective in achieving their purpose.

Recommendation:

U.S. Treasury and Department of State should undertake an assessment of the impacts on currently sanctioned countries and locations, to be provided to the National Security Council. A requirement for such an assessment should accompany all new Executive Orders for sanctions programs. This should include:

- impacts on civilian populations including access to clean water, sanitation, public health services, and food supply chains; changes in general mortality rate, maternal mortality rate, life expectancy, rates of infectious diseases, rates of malnutrition and stunting, and literacy;

- environmental impacts experienced by the country including crop production, soil fertility, energy consumption, and fossil fuel usage;

- the delivery of humanitarian aid and/or development projects in the country;

- rates of migration including any increase or decrease in refugees or migration from the country or internally displaced people in the country;

- economic, political and military impacts;

- reactions of the country to imposed sanctions, including policy changes and internal sentiment;

- the degree of international compliance and non-compliance of the country.

In addition, impact assessments should include the following information regarding impacts on U.S. policy and U.S. security:

- Impact on U.S. national security;

- Whether stated foreign policy goals of sanctions are being met;

- Degree of current or anticipated international support or opposition;

- Degree of compliance of sanctions regime with international law- including compliance with provisions of UNSCR 2462;

- Impact on U.S. economy, businesses, and consumers;

- Impact on financial institutions and suppliers working with humanitarian actors in sanctioned locations;

- Criteria for lifting sanctions; Prospects for fully enforcing sanctions.

2) Improve licensing transparency and procedures

The licensing process at the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is dysfunctional and overwhelmed. The Charity & Security Network (C&SN) report Safeguarding Humanitarianism [10] explains, “…although there is a licensing process that allows the Treasury Department to make exceptions under one set of regulations for limited humanitarian action, this process is often described as excruciatingly slow and ineffective. It lacks any consideration of international law in its decision-making procedures. The licensing regime contains no explicit exceptions for critical humanitarian assistance. If a license is granted, the conditions of it may compromise the core operating principles of humanitarian organizations, particularly neutrality. The result of such a process is to make addressing urgent humanitarian need the exception, rather than the rule.”

While General Licenses issued by OFAC exempt some humanitarian trade from sanctions, they are often insufficient to meet all of the needs of a humanitarian response. For example, there is no General License exempting certain crucial devices and equipment for COVID-19 prevention, diagnostics, and treatment in Iran. These require special licenses, which can take up to an average of 77 business days for approval by OFAC. In some contexts, such as North Korea, aid agencies report the process taking anywhere from nine months to three years.

Recommendation:

U.S. Treasury should take concrete steps to make the licensing process more efficient increase transparency for both applicants and the public.

Transparency for the license applicant:

In all specific license applications, the applicant shall be supplied with the name and contact information of the OFAC official responsible for processing the application. Decisions shall be made in writing. In cases where a license is denied there shall be an explanation of the reasons for the denial and information on the process for reconsideration. The standards for approving licenses for humanitarian assistance and peacebuilding projects shall be clearly defined, available to the public, consistent with humanitarian principles and promote effective programs by being sufficiently flexible to ensure that applicants can conduct their activities with impartially, speed and discretion. The independence and neutrality of humanitarian assistance programs will be respected, and as such, not be compromised by political or foreign policy considerations. To avoid undue delays that might jeopardize the viability of a proposed humanitarian, development or peacebuilding projects, OFAC shall review each application within a reasonable time and either grant or deny the license. If, after a reasonable time has elapsed from submission of the application, OFAC has not yet made a determination, then the applicant may proceed with the plan described in the application. If OFAC rejects the license after such work has begun, the applicant may not be prosecuted or sanctioned for any such activities that it conducted between the 91st day and the time at which it is informed of the denial. In the case of a declared humanitarian emergency the applicable period of time will be seven days.

Transparency for Congress and the public:

- Provide the number of specific licenses related to humanitarian assistance issued by the Office of Foreign Assets Control;

- Provide the number of requests for specific licenses related to humanitarian assistance denied by the Office of Foreign Assets Control with explanations for the denials;

- Provide the number of requests for specific licenses related to humanitarian assistance that have been pending for 30 days or more;

- Provide the number of requests by persons who are not U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, or entities, for sanctions waivers related to humanitarian assistance that have been pending for 30 days or more as of the date of the report, with explanations for the delays.

3) Issue a Global Temporary General License for Duration of the Covid-19 Pandemic

The current COVID-19 pandemic highlights the precarious and, in some cases, critical state of the health infrastructures and economies of these sanctioned locations, and how, without immediate intervention, millions of people face severe economic hardship, infection, and death. We urge the new administration to enact the principles put forward in a letter to Secretary Mnuchin and Secretary Pompeo from Senator Warren, Representative Garcia and over 70 other members of Congress to issue a temporary global general license to expedite COVID-19 related aid. There is bipartisan precedent for such an act; for example, President George Bush issued such a license in the wake of an earthquake in Iran in 2003. We support UN Secretary-General António Guterres in his call “for the waiving of sanctions that can undermine countries’ capacity to respond to the pandemic.”

Recommendation:

Specifically, we urge you to issue emergency universal exemptions for humanitarian goods. The exemptions could take the form of an emergency universal general license that would allow humanitarian agencies to respond to the crisis quickly and more effectively.

The license would need to, at minimum, exempt:

- Aid necessary for the treatment of COVID-19;

- Equipment used in the recovery from the disease;

- Goods required to address simultaneous needs and issues exacerbated by the pandemic such as food security, water supply, civilian energy infrastructure, and other health-related needs such as medical kits and equipment;

- Necessary training required for the use of medical and humanitarian equipment;

- Communication and partnerships with non-sanctioned organizations and individuals. (These exemptions would be necessary for contexts such as North Korea where a specific license is required for partnerships with nonsanctioned organizations and individuals).

- Transactions and communications ordinarily incidental and necessary to accessing civilian populations in need of assistance.

Finally, the universal general license must address the reluctance of financial institutions, as well as other entities within supply chains, to carry out transactions required for the delivery of this aid.

Endnotes

[1]https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/nrcprinciples_ under_pressure-report-screen.pdf

[2] Holder et. al. v. Humanitarian Law Project et. al., 130 S.Ct. 270, 177 L. Ed. 2d 355 (2010).

[3] USAID Mission Order 21

[4] 50 USC §1702(b)(2)

[5] For example, see EO 13886 (Sept. 10, 2019), updating EO 13224 (Sept. 25, 2001, concerning counter-terrorism financing); EO 13536 (April 12, 2010, establishing the Somalia sanctions).

[6] See 50 USC §1702(b)(2), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/1702

[7] EO 13224 (Sept. 25, 2001)

[8] EO 13224 stated in Sec. 4: “I hereby determine that the making of donations of the type specified in section 203(b)(2) of IEEPA (50 U.S.C. 1702(b)(2)) by United States persons to persons determined to be subject to this order would seriously impair my ability to deal with the national emergency declared in this order, and would endanger Armed Forces of the United States that are in a situation where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, and hereby prohibit such donations as provided by section 1 of this order.”Similarly, EO 13536 stated, in part: “(c) I hereby determine that, to the extent section 203(b)(2) of IEEPA (50 U.S.C. §1702(b)(2)) may apply, the making of donations of the type of articles specified in such section by, to, or for the benefit of any person whose property and interests in property are blocked pursuant to subsection (a) of this section would seriously impair my ability to deal with the national emergency declared in this order, and I hereby prohibit such donations as provided by subsection (a) of this section.”

[9] See Charity & Security Network “Deadly Combination: Disaster, Conflict and the U.S. Material Support Law” April 2012. Available online at https://charityandsecurity.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/06/deadlycombination.pdf

[10] Charity & Security Network Safeguarding Humanitarianism in Armed Conflict July 2012

[11] Charity & Security Network, Financial Access for U.S. Nonprofits, www.charityandsecurity.org/FinAccessReport

[12] For example, a U.S.-based NPO planned to carry out a winterization program in Afghanistan, but it was never implemented because by the time the funds were transferred, winter was over. (p. 81-82) Another U.S.-based organization was prevented from sending immediate relief to the Rohingya minority in Myanmar in the midst of a dire humanitarian crisis. (p, 50) Charity & Security Network, Financial Access for U.S. Nonprofits, www.charityandsecurity.org/FinAccessReport

[13] Ibid, p. 94.

[14] Ibid, p. 40.

[15] The fact that NPOs are subject to a complex system of regulation and oversight at the federal, state and local levels, and required to register and be monitored by the IRS and state authorities is not well-understood. In addition to reporting requirements, many NPOs also adhere to voluntary self-regulatory standards and controls to improve individual governance, management and operational practice, beyond internal controls required by donors and others. These regimes primarily regulate raising, spending and accounting for funds, seek to protect the public from fraud, and encourage charitable giving. NPOs receiving federal grants undergo additional review by grant making agencies to comply with standards required by OMB (e.g. Agency for International Development recipients are subject to rigorous scrutiny, compliance, and independent auditing requirements). See Sue Eckert, International and Domestic Implications of De- Risking, Testimony before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit, Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, June 26, 2018, at https://charityandsecurity.org/system/files/Eckert%206_26_18%20Final%20Statement.pd